One of the most popular Fortune articles in many years was a cover story called: “What It Takes to Be Great.” Geoff Colvin offered new evidence that top performers in any field — from Tiger Woods and Winston Churchill to Warren Buffett and Jack Welch — are not determined by their inborn talents. Greatness doesn’t come from DNA but from practice and perseverance honed over decades.

“The best performers set goals that are not about the outcome but about the process of reaching the outcome.”

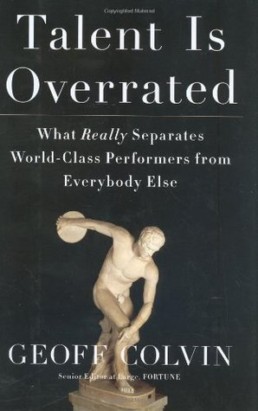

– Geoff Colvin, Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else

Not just plain old hard work, like your grandmother might have advocated, but a very specific kind of work. The key is how you practice, how you analyze the results of your progress and learn from your mistakes, that enables you to achieve greatness.

Now Colvin has expanded his article with much more scientific background and real-world examples. He shows that the skills of business: negotiating deals, evaluating financial statements, and all the rest, obey the principles that lead to greatness, so that anyone can get better at them with the right kind of effort. Even the hardest decisions and interactions can be systematically improved.

This new mind-set, combined with Colvin’s practical advice, will change the way you think about your job and career, and will inspire you to achieve more in all you do.

“What great performers have achieved is the ability to avoid doing it automatically.”

“Deliberate practice requires that one identify certain sharply defined elements of performance that need to be improved, and then work intently on them.”

“The best performers set goals that are not about the outcome but about the process of reaching the outcome.”

“The best computer programmers are much better than novices at remembering the overall structure of programs because they understand better what they’re intended to do and how.”

“Mozart’s first work regarded today as a masterpiece, with its status confirmed by the number of recordings available, is his Piano Concerto No. 9, composed when he was twenty-one. That’s certainly an early age, but we must remember that by then Wolfgang had been through eighteen years of extremely hard, expert training.”

“When top-level chess players look at a board, they see words, not letters. Instead of seeing twenty-five pieces, they may see just five or six groups of pieces. That’s why it’s easy for them to remember where all the pieces are.”