It’s not uncommon for anyone even remotely interested in art to have an interest in the life and work of Leonardo Da Vinci. Nor is it uncommon for creatives to have a thing for peering into the sketch books of others to satisfy a creative curiosity as to how someone thinks and develops their ideas. I know I fall hard into both camps, so I thought I might bring the two together. Let’s have a look at the brilliant sketchbooks of the old master.

The power of Leonardo’s works is undeniable. While he may have only produced a handful of finished pieces, the impact he left is second to none. Below are the sketches for two of the most well known and renowned pieces of creative work the world has ever known.

These illustrations move me. Not because of what they are depicting, but because of the quality and care and craft that was put into them.

As a graphic designer, I have a love for seeing the sketch books of creatives, as I’m sure you do too. There’s something to looking into the development of a piece of work you admire — to see how it was constructed, how the idea came to fruition—it’s interesting and exciting.

The notes are mostly observations or little tidbits I read while putting this all together, that make the imagery a little more interesting.

The Last Supper

Easily in the top two of Leonardo’s most renowned pieces, The Last Supper was commissioned by his employer of the time, the Duke of Milan, in 1495 and took three years to complete.

While the painting has deteriorated horribly over the years, what makes it so special is so easily seen — the emotion and expressions strewn across the faces of those at the table are stunning. The detail in their skin, hair and clothes are of such high quality and rich detail that it can be hard to easily understand the depth and complexity emotion and body language shown.

Let’s start with a good look at the finished product. This is the moment in the Biblical story that Jesus says that he will be betrayed by one of those sitting with him. Looking closely at the expressions, you’ll noticed surprise, anger, fear and sadness, which up to this point weren’t always shown in such legitimately human ways in previous representations of this scene by other artists.

Now moving on to the sketches! This was an initial draft done hastily to establish position and proportion, done as if he had excitedly realised how he was going to compose the image.

I love this one for so many reasons. It’s a considerable step up from the previous scrawl, but is still just reference — and it’s stunning. The fact that he started at one spot of the page, made his way left and ran out of room is refreshing. There is something humbling in realising that even a genius makes mistakes.

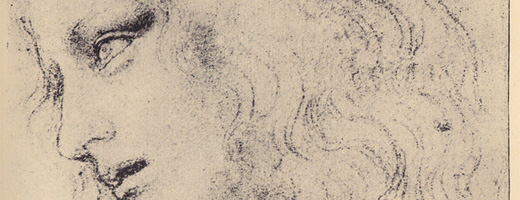

This is an early sketch of St James the Greater, clearly focusing on the emotion that is carried through the expression on the face. In the final, he is sitting second on the right from Jesus. This is one of the sketches that is fantastic to see as it helps give a better understanding of the expression in the fresco.

The model used for the previous sketch of St John, as well as this one of St Philip were one in the same. While the expression is more visible in the final than the previous (St Philip is fourth from the right), the value of the emotion in the eyes is one of the best in all of the sketches featured here.

Judas, third from the left wearing the green and blue robe — the composition and expression in this sketch is very close to the one he wears in the final. The muscle tone is just breath-taking and the expression in the ridge above the eye is intriguingly powerful.

This sketch for St Bartholomew isn’t much different in style than many other portraits by the Great Master — in fact it’s less detailed and less impressive than most, but as always the eyes have something special in them. In the final, St. Bartholomew is on the far left, scorning a view across the table that, which when paired with the detail of this sketch, is easily felt. The dark, suspicious eyes with the brow buried in contempt, coupled with the down-turn in the edge of the lip make this one of the best expressions of emotion here.

This sketch of St. Peter sits in a nice spot between the previous sketches and the final, chronologically speaking. By now, you’ve probably noticed that none of the previous sketches have beards, but in the final, the almost all do. The composition in the final is quite a bit different than this one, as you’ll notice the final is more of a profile than this. This is also one of the few sketches that shows more attention being paid to the clothing and overall composition, which, in this version, I actually prefer over the final. In the final, he is fifth from the left, reaching behind Judas.

As I’ve said over and over, take special note of the eyes and the age and emotion they show.

One more time, the final.

The Virgin and Child with St Anne (and John the Baptist)

This is a scene which Leonardo had thought about more than once. While there is only one finished product, there is another line of research and development done for an earlier piece, The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist.

Because the two images are concerned with the same theme and hold almost the same composition, I thought it would be worth-while to include sketches for both.

The two artworks that came out of his interest in this theme was the cartoon of The Virgin and Child with St Anne and John the Baptist, also known as the Burlington House Cartoon, and the final painting which was The Virgin and Child with St Anne.

The Burlington House Cartoon was his first attempt at this scene, and never became more than a large illustration. The second piece was completed eight years after the initial sketches were done. Why eight years? I’m not sure, to be honest. The painting was done at a different time in his life, when his interests were swung away from art and landed on mathematics and geology. Perhaps Freud’s theory (below) was right and he became sentimental as he got older?

While the detail in the clothing is engaging and the muscle and flesh tone amazing, it’s the emotion in both of these pieces that make them enticing. The love and admiration held for one another is truly warming, as they each gingerly gaze at one another in succession — St Anne smiling at her daughter Mary, Mary at her son — they are proud of what they have given life to.

Freud had suggested that the reason why Leonardo had a fondness for this scene, the depiction of the two mothers in particular, is due to his upbringing. At first cared for by his blood mother, he would go on to be adopted by the wife of his father. What helps give a little bit of legitimacy to this theory can be seen in the age of the two women, who appears much closer than a mother and daughter might.

An almost unintelligible mess this illustration became. Clearly trying to work the mixing of arms and fabrics and bodies over and over, Leonardo pushed this to a point where it is nothing much more than a scribble. What’s interesting about it, is that the layout appears to be somewhere between The Burlington House Cartoon and the oil painting.

This is a development illustration that would become the final oil painting as it is one of the first to introduce the lamb, but was quite possibley done when developing the cartoon, rather than the oil painting. It seems as if he did a lot of the ground work for this theme, but abandoned it at some point, only to come back to it later in his life, resulting in the final.

This illustration for The Burlington House Cartoon is interesting because of the marks around the edge of the figures and the almost undecipherable scratches for the lower parts of the bodies. Both of these were because of Leonardo trying to find a satisfactory manner in which to have them sit in space.

The Burlington House Cartoon. This is as far as Leonardo came with this exact scene and the four people it portrays. As I mentioned earlier, it’s the gazes that each person is throwing to the other that make this so beautiful.

Detail of the face of St John from the Burlington House Cartoon. One of the things that Leonardo did so well, in my opinion, is hair. I’m not sure why, but these ringlets of hair as drawn here are just fantastic.

Detail of the face of Mary. The softness of her skin can be felt through the gentle shading around the cheek bone, with the half closed eyes in her son’s direction, there is such a delicate feeling to her expression.

St Anne looking on at her daughter, as she looks at her son. The delicateness isn’t quite as soft as that of Mary and when looking at them closely, it’s hard to determine what kind of age gap there is, giving a point to Freud’s theory.

Where as with Jesus, the hair isn’t of the same quality, but the facial expression and the shading around the eyes, nose and the bottom of the cheek are great.

And of course, here is The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, as a finished oil painting.As you’ll clearly notice, St John is no longer included and instead, the baby Jesus is wrestling a lamb. This painting was done when Leonardo was starting to venture into other grounds, outside the walls of the art world, which is why this is apparently unfinished.

More Sketches

I was originally going to look at three works by Leonardo but decided against it as, at this point, the article is obviously quite long and I wasn’t going to be able to get everything into it that I wanted. So rather than trying to squeeze another lot of development work and a final piece into this article, I thought I would just share with you a few sketches that really grabbed me. They range from art to science, math to engineering.

Master Your Craft.

Weekly.

Become the designer you want to be.

Join a group of talented, creative, and hungry designers,

all gaining the insight that is helping them make

the best work of their lives.